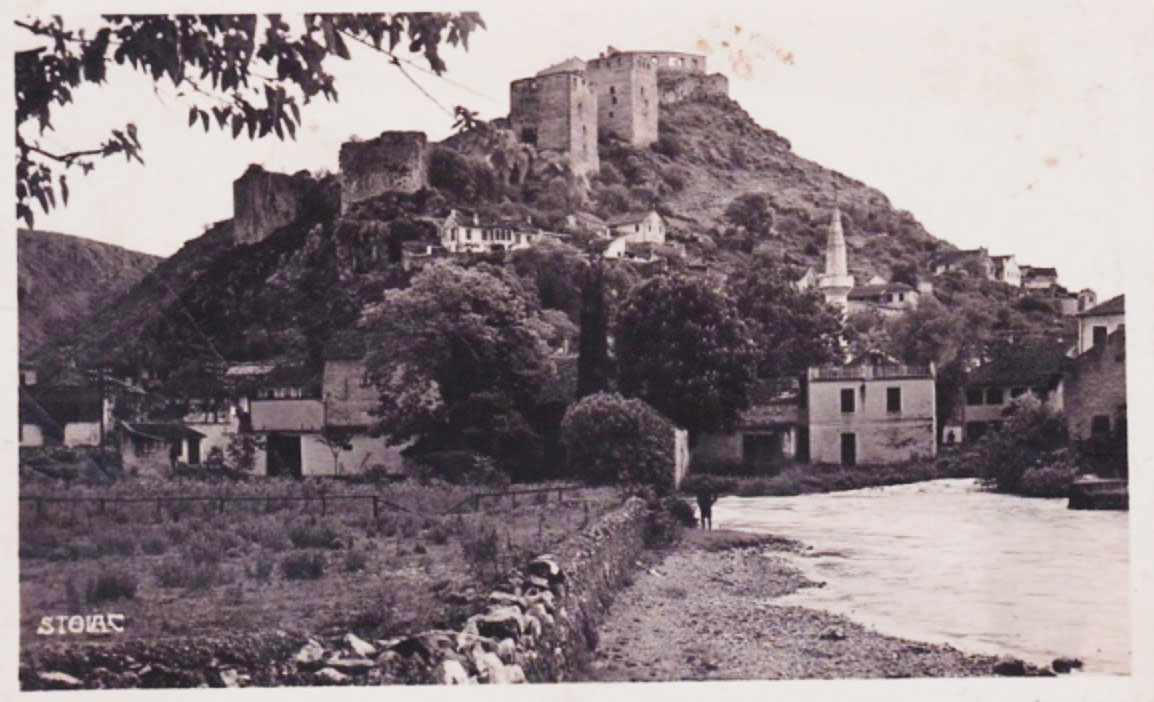

Story of Fahrudin Rizvanbegović is unavoidable when promoting Stolac in all of its glory. He is one of the living “trademarks” of this marvelous town. Descendant of the so important and influential family he continued with a tradition of living in Begovina. Fahrudin is a retired professor of Bosniak literature.

While studying in Zagreb, and being a member of the 1968 “rebel generation” when preparing his thesis defence he asked for impossible. “Be realistic, ask for impossible” was a motto of that generation. Therefore, in accordance with that he proposed a politically very delicate thesis: “Mak Dizdar – Bosnian writer”. Two years before that in 1966, Mak Dizdar published his epochal book of poems “Stone sleeper”. This literary work made him a top-rated poet in Yugoslavia at that moment. Dizdar was born in Stolac as well, thus it was infinitely important for one small community to brag with such success.

In that time, Bosnian literature within Yugoslav scientific circles haven’t existed. Only Serbian, Croatian and Slovenian. Somehow, Mak Dizdar was put into a Croatian component of the Yugoslav literature. Ironically, his brother Hamid Dizdar, also a writer, ended up within Serbian component. While provoking unfair organization, his professor allowed him to successfully bring his thesis defense to an end.

An interesting anecdote took place in these times. Fahrudin wanted to make out of his home in Begovina a literary saloon, which he managed to do later on. But first, he wanted to host a poet star Mak Dizdar in his house. When they arrived, Fahrudin’s father asked him: “Why did you bring this billy goat here?” Mak truly had a specific “goat beard” and that was one his trademarks. After that joke, he realised his father knew Mak pretty well from high school times.